In 2022 G.A.S. received a donation of a lifelong personal library collection from Professor John Picton and Sue Picton. Its scope includes the visual arts of Sub-Saharan Africa (sculpture, masquerade, textiles), publications dealing with history and archaeology (including Saharan rock art); as well as African American and Black British arts, and more. The books totalling some 1500 volumes have been collected over a period of decades and in that time have been a crucial resource for both Picton and his students. In 2023, the collection will continue its journey from the Picton family home in Evesham, England to Lagos, Nigeria where it will once again become a point of reference for those wishing to enrich and deepen their knowledge of African history and visual culture.

John Picton's relationship with Nigeria began in 1961, a year after the country gained its independence from British rule while Sue Picton first arrived in the country in 1968. Much like their personal archive, their relationship with Nigeria has continually developed and endures to the present day. As the library collection begins a new life in Lagos, Professor John Picton and Sue Picton reflect on the moments that were pivotal to its inception and evolution.

For those that may be less familiar with your career, could you please elaborate on your personal connection to Nigeria, and in particular its visual culture?

John Picton: I was offered employment by the Federal Government of Nigeria in what was then called the Department of Antiquities, within the Ministry of Education. My professor at University College, Daryll Forde, had met Bernard Fagg, the Director of the department who said he was looking for someone to take over as curator of the Nigerian Museum, Lagos. Forde recommended me! Goodness knows why! But I soon received a letter from Bernard telling me he’d like to offer me a post in Nigeria, but first I had better work with his brother William at the British Museum and learn about Nigeria.

It so happened that William Fagg was the leading pioneer of the study of African art in the UK; and from 1958-59 he had been working in Nigeria for the Yoruba Historical Research Scheme, during which time he also made a collection of Yoruba art that was divided between the Lagos Museum, and the British Museum. Now, at that time, the process of registering incoming collections in the British Museum involved drawing each object and giving it a written description in a mighty leather-bound ledger; and so I was put to work drawing the collection Bill Fagg had made for the British Museum. As it happens, I was used to drawing as my favourite A-level at grammar school was zoology. This was at a time when each boy got his own rat, earthworm, frog, dogfish, etc., to dissect, and having opened the thing up one had to draw one’s findings. So, turning back to William Fagg and the British Museum, by the time I had drawn this collection, I knew, more-or-less, what to expect at least in terms of Yoruba traditions of sculpture; and he also made sure that I was able to study the reserve collections at the British Museum such that by the time I arrived in Nigeria in June 1961, I knew my way around the country at least in terms of its traditions of sculpture.

From L-R: Bell form; clapperless Janus faced horned bell head lost-wax cast in copper alloy, Figure; male figure seated on a low stool lost-wax cast in copper alloy, Figure, human head; lost-wax cast in copper alloy. All objects from the Nigerian Tribal Art collection collated by William Fagg. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

I was interviewed at the Nigerian High Commission and soon found myself on a plane to Nigeria. I was sitting next to Felix Ibru - I think he was on his way home from university, and I know he became famous in Nigeria’s refrigeration industry. I was 22 when I arrived, and somewhat alarmed to discover I was in charge of some 40 staff. I lived in Force Road just across from the museum, and as curator, I could go in at any time, day or night, and study the reserve collections - the finest collection in the world of the art traditions of Nigeria, put together by the museum’s founder, Kenneth Murray, who still lived in Nigeria, across the mouth of the lagoon: one could only get there by boat.

Also, the offices of Nigeria magazine, with its exhibitions centre, were just along the Marina from Force Road, and there was a continual programme of exhibitions of contemporary art, from Nigeria, Ghana, Mozambique, Sudan, and African America. I encountered the work of Uche Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Vincent Kofi, Malangatana, Ibrahim El Salahi, and Jacob Lawrence, and discovered that the art in the museums was not the only art being made, that local modernisms were already there, reckoning with social and political conditions, colonial and racial prejudice, whilst also drawing upon the repositories of antiquity as well as tradition, by which I mean the inheritance of a more recent past. I began to see how, in the relationship between the inheritance of the past and contemporary developments in art-making, there were continuities as well as discontinuities – the history of art was ever thus!

Map detail of Lagos Island, 1962.

Map detail of Lagos Island, 1962.

Moreover, when I arrived in Lagos in 1961, I had not yet learned to drive and did not possess a motor vehicle, if I was going anywhere not on official business I either walked, took a bus, or haggled with a taxi driver; and as ‘office hours' were 8am-2pm, once I’d had my lunch my time was my own.

I often returned to the museum, but I also began walking through Lagos Island, taking in the Brazilian quarter, Okepopo, Jankara market and Isale-Eko, finding out about gelede and its masked performances in the area behind the king’s palace, as well as egungun, the ancestral masks brought into Okepopo (which was also where the araba, the chief diviner on Lagos Island lived), as well as the adamu-orisha funerary commemorations of elite Lagos Island. I was also able to visit Kano and Jos, and saw rock paintings I forget where in northern Nigeria, excavations in Ife, arts centres and colleagues in Ibadan and Oshogbo, and the sculptural traditions of North East Ekiti and Opin in the company of Fr Kevin Carroll, renowned for his work in employing local artists in the Nigerianisation of the visual arts and statuary necessary to Catholic churches.

The National Museum of Lagos. Image credit: The Independent, Nigeria.

The National Museum of Lagos. Image credit: The Independent, Nigeria.

And all this was achieved in my first tour of duty, from June 1961 until March 1963, during my home leave, I also visited Paris together with both William and Bernard Fagg to stop the sale of a group of Yoruba sculptures which had been removed illegally from Nigeria; and because of all the information I had gathered together, I was able to identify the places from which each work had been stolen, and thereby secure their return to Nigeria.

For my second tour of duty, from September 1963 until March 1965, I spent the first three months in Jos assisting Bernard Fagg in the administration of the department as he prepared to leave and take up a post as curator of the Oxford University Pitt Rivers Museum. After Christmas and New Year in Lagos I moved to Ife (the archaeologist, Frank Willett, had moved back to the UK leaving his house vacant) in order to oversee the Ife museum, but, more importantly, begin a survey of works of art still in use in North Eastern Yoruba communities (Igbomina, Ekiti, Opin, Yagba, Kabba) also collecting no longer wanted works of art for the Lagos Museum.

For my third tour of duty, from September 1965 to November 1967, Kenneth Murray suggested I move to Okene and continue the kind of surveying and collecting I had been doing in North East Yoruba, in Ebira and the Niger-Benue confluence region. Having researched Yoruba sculpture, I found Ebira masquerade a fascinating contrast and a subject of still continuing interest. I also gave ethnographic training to a new Nigerian recruit, and I chose the Delta Igbo community of Ahoada which neither of us knew. In 1967 I moved back to Lagos to assist Ekpo Eyo, the newly appointed Director of Antiquities, combining the roles of Senior Ethnographer and acting Deputy Director.

Image from ON (MEN?) PLACING WOMEN IN EBIRA. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. PICTON, JOHN. (2006).

Image from ON (MEN?) PLACING WOMEN IN EBIRA. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. PICTON, JOHN. (2006).

For my fourth and final tour of duty, from April 1968 until January 1970, I was based in Lagos as acting Deputy Director, but taking time out in order to return to Ebira at festival times to continue my work with Ebira masquerade. In July 1968 Sue Connell, another new recruit, arrived in Lagos and needed training before I dispatched her on ethnographic survey work in Akoko-Edo and, later, North West Igala.

However, neither Sue nor I returned to Nigeria after coming on leave in early 1970 as we married, and I was offered a post at the British Museum. And when we did return, it was part of a journey which, in 1971, took in Algeria, Niger and Burkina Faso, as well as Nigeria, together with our daughter, Josephine, who had been born in November 1970. We were to return as a family again in 1982, this time also with our son, Matthew, born in July 1972. I have made other visits to Nigeria in 1981, 1982, 1990, and 2022, and, in addition to the countries already listed, I have also visited Ghana, Kenya, Namibia and South Africa. But my experience of Nigeria has always been the basis of my work in the fields of African art studies.

The MV Aureol (named after a mountain in Sierra Leone), the ship that took Sue Picton from Liverpool in the UK to Lagos, Nigeria. Image copyright: Gordon Dalzell.

The MV Aureol (named after a mountain in Sierra Leone), the ship that took Sue Picton from Liverpool in the UK to Lagos, Nigeria. Image copyright: Gordon Dalzell.

Sue Picton: I had been taught by Indianists during my degree in Social Anthropology, but my curiosity about Africa was awakened and I was determined to find a way to work on that Continent. I moved to London and found temporary work teaching in a primary school while I looked for jobs in Africa. I found an advert for a museum worker in a North African museum that I discussed with a group of friends from university who lived nearby and discovered that one of them had been a VSO in Nigeria before her degree course where she found a well-developed museum service. She had become friendly with the then Director of Antiquities, Ekpo Eyo, who was about to visit her in London. I met him during this visit and he advised me to write to the Nigerian High Commission as there was a vacancy for a museum ethnographer, that required a degree in Social Anthropology! I did that and was called to an interview led by William Fagg and subsequently offered the post in late April 1968. I felt I had to finish the teaching term and was offered the chance to travel by boat in mid-July. I duly set off on the MV Aureol, one of the last Elder Dempster ships to sail from Liverpool to Lagos.

The late Professor Ekpo Eyo as he looked in the late 1960s.

The late Professor Ekpo Eyo as he looked in the late 1960s.

In Nigeria I found myself working for John Picton and Ekpo Eyo, and did fieldwork for the museum, helped with exhibitions and was inducted into the collections by Kenneth Murray who founded the Nigerian Museum Service. I completed my tour of duty in January 1970, returned to the UK, married John Picton and then volunteered at the British Museum for a year or so while it was planning its move to and exhibitions in the Museum of Mankind. We travelled back to Nigeria with our baby daughter in 1971, we then had our son Matthew in 1972 and it was not possible to continue my museum volunteering. While the children were young I worked freelance in publishing for Longmans on their Africa list, doing picture research, and copy editing textbooks at all levels from Primary School through to Higher Education. I was also able to use some of my fieldwork photos from my time working for the Nigerian Museum service and those taken In 1982 we all returned to Nigeria for a few months as part of John’s work for the Museum Of Mankind.

What are the origins of the archive collection that has now found a new home at G.A.S. Lagos?

JP: I was to remain at the British Museum until 1979 when I was offered a post at the School of Oriental & African Studies of the University of London to develop the teaching of African Art. While at the British Museum, I had been asked if I could present a one-term seminar for MA students at SOAS, and this had given me a taste for teaching. In Nigeria I had already acquired books and periodicals relevant to my work, while in the British Museum, I had access to the departmental library; but having been appointed to SOAS I realised that I had to expand my personal library so that the books I needed to read were also available to the students – and I also had to expand my interests beyond Nigeria to cover all aspects of the visual arts of Africa (other than Coptic and Islamic Africa, covered by other SOAS colleagues). Since my retirement at age 65 in September 2003, I have continued writing and the library that had been put together was invaluable, enabling me to work at home. But the time has now come to withdraw from all this, and turn my personal archives and photographs into a useable resource for others in their continuing research.

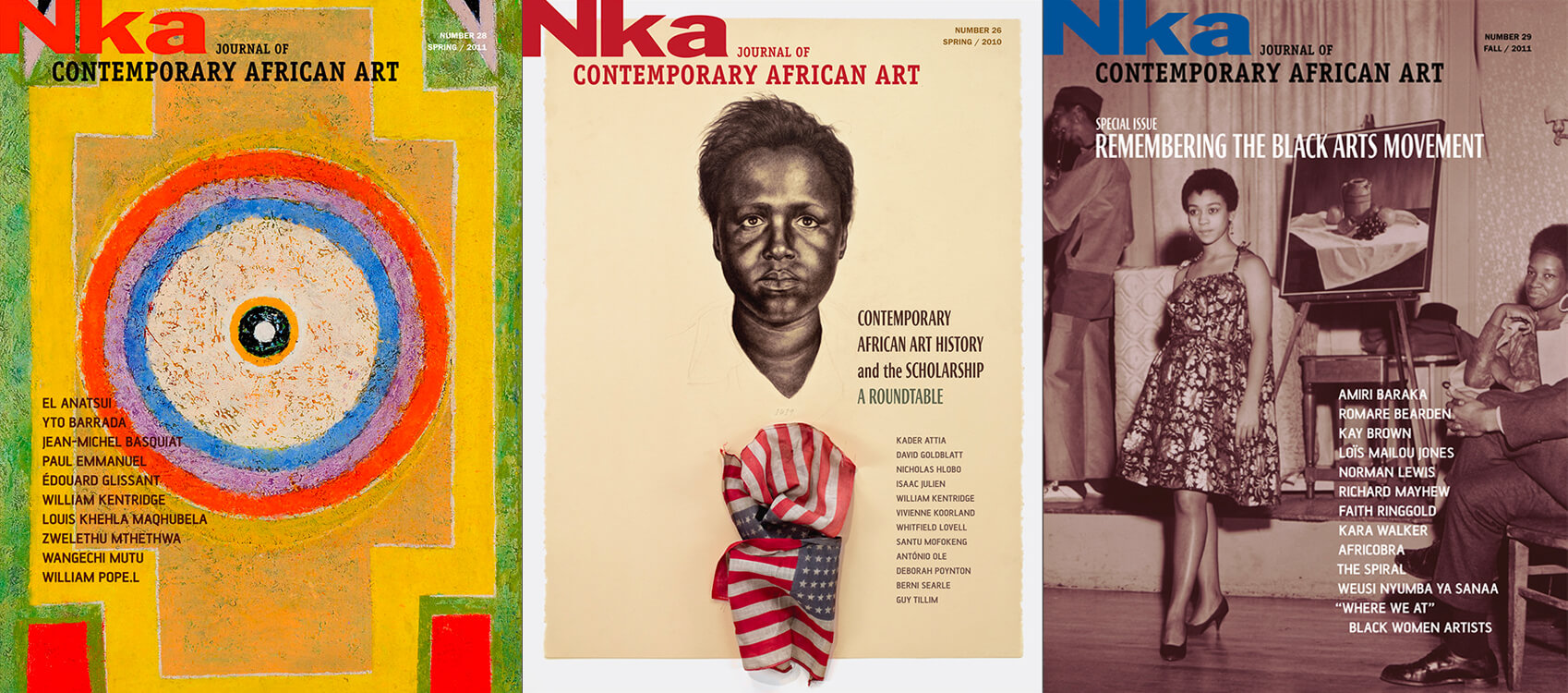

Covers of the Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art. The publication will form part of the Picton Archive at G.A.S. Lagos.

Covers of the Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art. The publication will form part of the Picton Archive at G.A.S. Lagos.

Can you spotlight any volumes that you’ve returned to frequently for your own research?

JP: The most useful single resource is African Arts, a quarterly journal produced originally by the UCLA African Studies Department, beginning in about 1968. This charts the development of African art studies to its present condition which includes the archaeological past as well as the contemporary present, the inheritance of forms of sculpture, masquerade, textiles, etc., from the more recent past, and the African presence in Europe and the Americas. I would like to think that as a group of scholars from all parts of the world, we have worked positively towards the decolonisation of the study of African art well away from its beginnings within misbegotten ideas of “primitivism” etc.

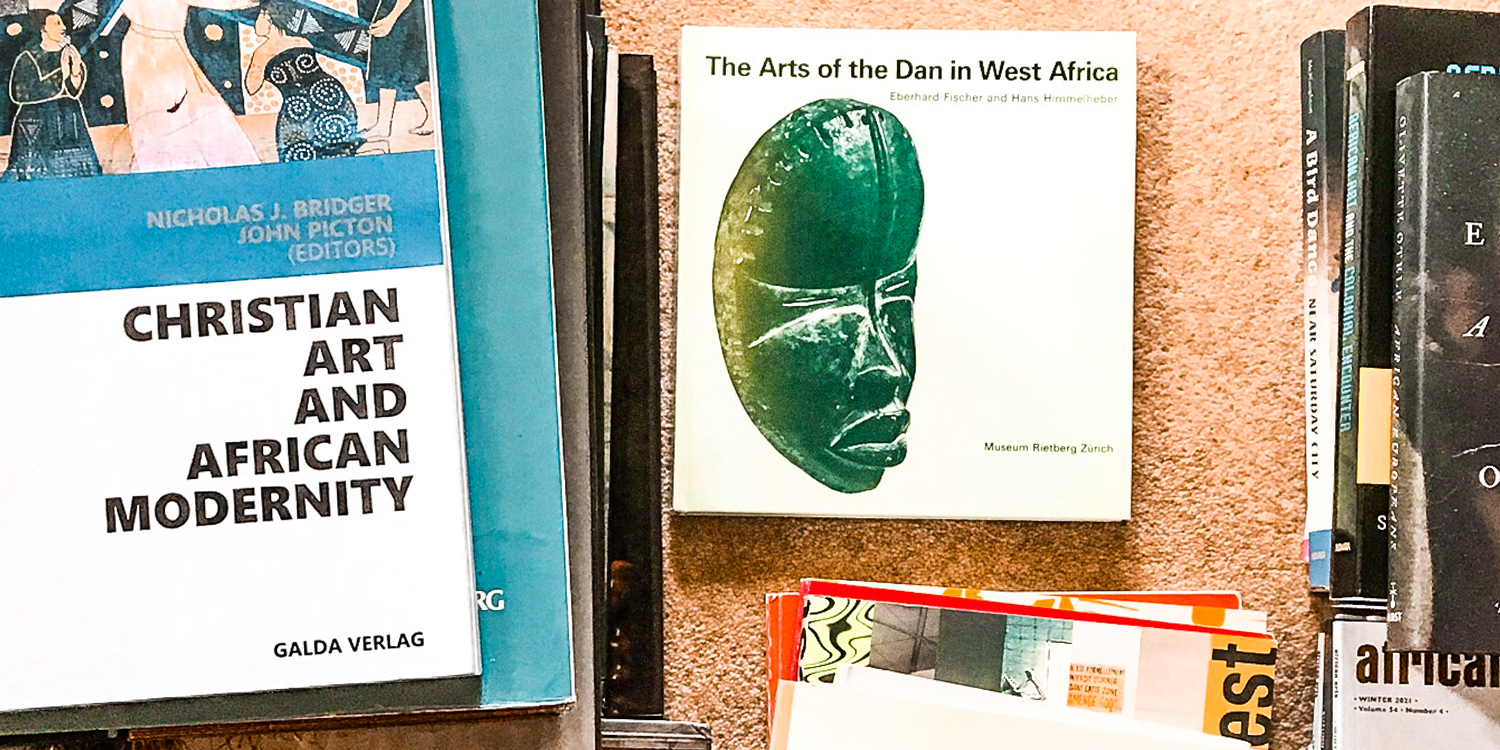

Books from the Picton archive being prepared for cataloguing and shipping to Lagos. Photo credit: Naima Hassan.

Books from the Picton archive being prepared for cataloguing and shipping to Lagos. Photo credit: Naima Hassan.

You’ve long been involved in the dialogue around restitution and repatriation and what that might mean for Western museums and institutions. Do you think the Picton Archive could be used to contribute to those conversations from within the continent?

JP: In 1897 several thousand works of art in cast brass, ivory, iron, ceramic, leather, woven textile and beadwork were removed as loot by British forces in Benin City to end up scattered through museums and collections all around the world. No records were made as to where in the royal palace these works of art had been located, and, in any case, the palace was burned down; so these works of art cannot simply be returned to where they once were. Moreover, as works of art from Benin City became known internationally, they, together with material from other countries, especially Ghana, Mali, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, etc., established that African antiquity was as great and glorious as any world civilisation. This is why Africa is well served by an African presence in major international museums. However, this must not be at the expense of those who are the modern-day inheritors of these civilisations: they too need to know of the glories of their past. As it happens, the Lagos Museum has the third most comprehensive collection of Benin City art (after the British Museum and Berlin) purchased by the colonial government mostly in the 1940s and 50s; but this is not good enough. So, three things are needed: i. recognition of local African ownership of these looted works of art; ii. negotiation whereby museums such as the British Museum can have on more-or-less permanent loan the works of art considered necessary for adequate representation of an African antiquity; and iii. the development of state-of-the-art museum facilities to house the material to be returned – and this has to be done as a matter of international cooperation and funding. But all this demands research, and this is where the library will be useful.

What are your hopes for the Picton archive as it begins its second life in Nigeria?

JP: Nigeria gave me a career; we hope that this library will provide a stimulus to others whether in art-making or in the research needed to understand local forms and values.

John and Sue Picton at their family home in Evesham. Photo credit: Naima Hassan.

John and Sue Picton at their family home in Evesham. Photo credit: Naima Hassan.

ABOUT JOHN PICTON

John Picton is an Emeritus Professor of African Art at the University of London, and a professorial research associate in the Department of Art History and Archaeology, School of Oriental and African Studies, where he was teaching and writing from 1979 to 2003 when he retired, in accordance with the rules then in force. He was also Visiting Associate Professor in the Art History Dept, UCLA, in the Fall Quarter, of 1987. Having been appointed to develop the teaching of African art in SOAS at a time when the teachers of archaeology and art history were scattered through one or other of the five language departments, and following up on his UCLA experience, he negotiated bringing these teachers together in the formation of an Art History and Archaeology department.

He was previously employed by the British Museum, 1970-1979, and by the Department of Antiquities (now the National Commission for Museums and Monuments) of the Federal Government of Nigeria, 1961-1970. He was educated at Cheltenham Grammar School (1949-1956) and University College London (1956-1959) where he studied Anthropology (social and biological + archaeology), with Zoology as a subsidiary subject.

His research and publication interests have included Yoruba and Edo (Benin) sculpture; masquerade; textile history; the inter-relationship of traditions and practices in the Niger-Benue confluence region of Nigeria with particular reference to Ebira and Akoko-Edo; developments in sub-Saharan visual practice since the mid-19th century; and. whenever possible, working across an inter-disciplinary context that entails social anthropology, archaeology and material culture, history of art, and comparative ritual practice. In 2010 he advised the British Museum in regard to their exhibition of antiquities from Ile-Ife, while also working with UCLA colleagues on their 2011 exhibition about the Benue Valley region of Nigeria, which, sooner or later, he intends to follow with a book about Ebira masquerade, one of the traditions of that area.

He was presented with an ACASA Leadership Award at its Triennial Symposium, Virgin Islands, May 2001 (the Arts Council of the African Studies Association is the most comprehensive world body of Africanist art scholarship); and was awarded an Honorary Fellowship of the Pan-African Circle of Artists at its 4th Biennale in Lagos, October 2002.

ABOUT SUE PICTON

Sue Picton is now retired but has worked as a museum ethnographer, an education consultant for museums and galleries, and a part-time lecturer in further and higher education. Her interests lay in responding to issues of difference and diversity, based on both disability and cultural heritage, and the development and implementation of frameworks and strategies for inclusion. On the one hand, she is a parent of an adult son and daughter (born 1970 and 1972 respectively), both of whom have multiple impairments, while on the other, her first experience as a museum professional was as an ethnographer for the Nigerian Museum Service. These personal and professional interests quickly became intertwined and underpinned her subsequent professional life. Her experience of and involvement with disability and cultural diversity issues both in and beyond the museum sector, on a personal and professional basis, have been wide-ranging and longstanding. Since retirement in 2002, she has continued active involvement in learning disability issues at a local, regional and national level, both in London where she lived until 2004, and currently in Worcestershire. She was also involved as a volunteer in a local museum for several years.

Sue Picton's professional career had to be part-time and flexible from 1970 - 1986, and part-time until 1995, due to caring responsibilities for her daughter and son who are now cared for in their own home. She has travelled extensively in the UK, Europe, North America and Africa and has lived in Nigeria and the USA with her disabled son and daughter. Museums and galleries have always featured in both her travels and personal life.